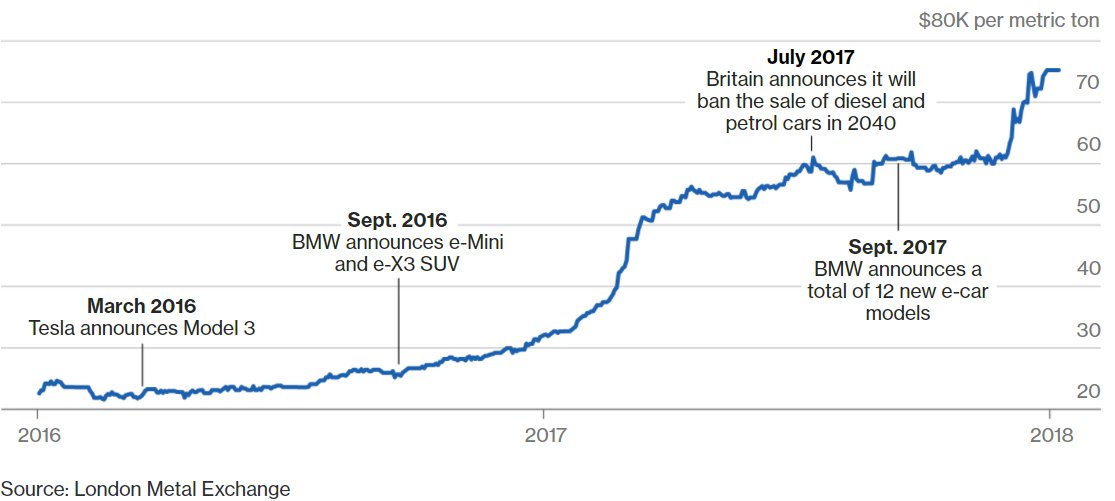

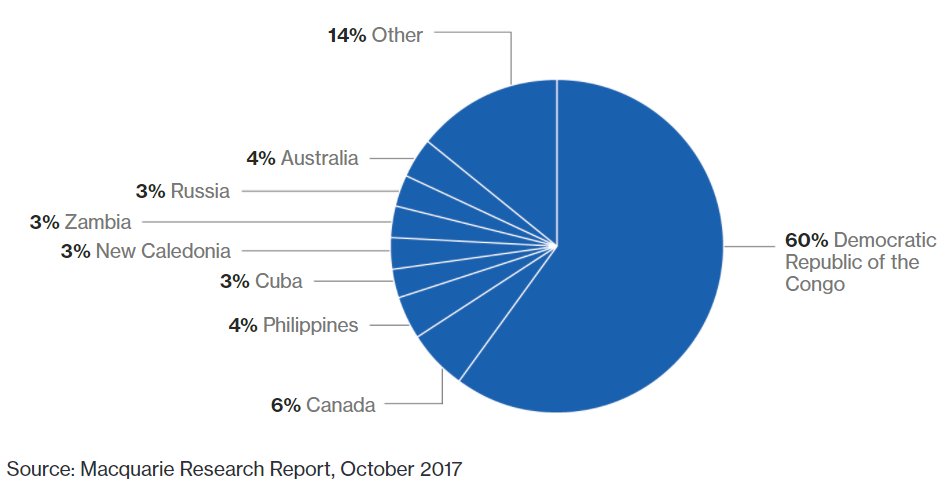

For carmakers vying to fill their fleets with electric vehicles, the spike has been a rude awakening as to how much their success is riding on the scarce silvery-blue mineral found predominantly in one of the world’s most corrupt and underdeveloped countries.

Rapid Rise

Cobalt prices stage one of the biggest jumps among commodities

“It’s gotten more hectic over the past year,” said Markus Duesmann, BMW’s head of procurement, who’s responsible for securing raw materials used in lithium-ion batteries, such as cobalt, manganese and nickel. “We need to keep a close eye, especially on lithium and cobalt, because of the danger of supply scarcity.”

Like its competitors, BMW is angling for the lead in the biggest revolution in automobile transport since the invention of the internal combustion engine, with plans for 12 battery-powered models by 2025. What executives such as Duesmann hadn’t envisioned even two years ago, though, was that they’d suddenly need to become experts in metals prospecting.

Automakers are finding themselves in unfamiliar—and uncomfortable—terrain, where miners such as Glencore Plc and China Molybdenum Co. for the first time have all the bargaining power to dictate supplies.

“They’re a lot bigger—but the reality is guys like us are holding all the cards,” said Trent Mell, chief executive officer of First Cobalt Corp., which is mining the mineral in northern Ontario and setting up talks with automakers seeking long-term supplies.

Mined Cobalt Output in 2016

Democratic Republic of the Congo dominates supply of the silvery-blue metal

The projections have made the lustrous metal, a byproduct of copper and nickel mining, into one of the most coveted commodities. Its price surged 128 percent in the past 12 months, in part because hedge funds including Swiss-based Pala Investments stockpiled thousands of tonnes of the stuff, which is used to power everything from mobile phones to home electronics.

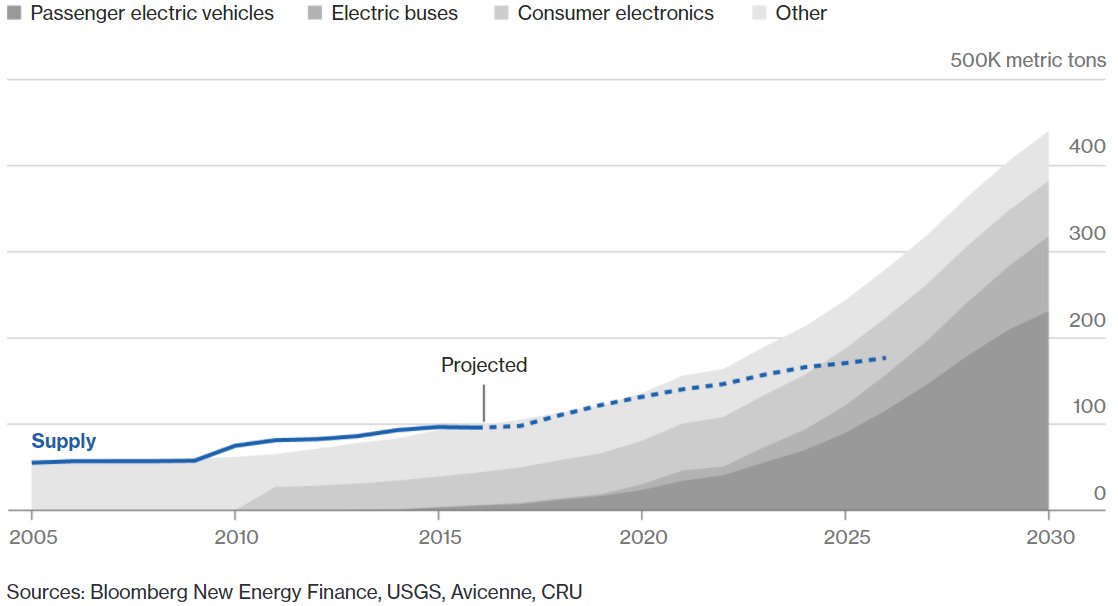

“There just isn’t enough cobalt to go around,” said George Heppel, a consultant at CRU. “The auto companies that’ll be the most successful in maintaining long-term stability in terms of raw materials will be the ones that purchase the cobalt and then supply that to their battery manufacturer.”

To adjust to the new reality, some carmakers are recruiting geologists to learn more about the minerals that may someday be as important to transport as oil is now. Tesla Inc. just hired an engineer who supervised a nickel-cobalt refinery in New Caledonia for Vale SA to help with procurement.

But after decades of dictating terms with suppliers of traditional engine parts, the industry is proving ill-prepared to confront what billionaire mining investor Robert Friedland dubbed “the revenge of the miner.”

Scarce Metal

As electric car production takes off, cobalt supplies are projected to fall short of demand

Duesmann said BMW is willing to pay upfront for a medium-term supply deal, one step short of taking stakes in miners. It’s also sending teams from its procurement and supply-chain sustainability departments to Congo this month, the third trip in a year. Aside from visiting big producers, they’ll explore the possibility of sourcing cobalt from artisanal mines.

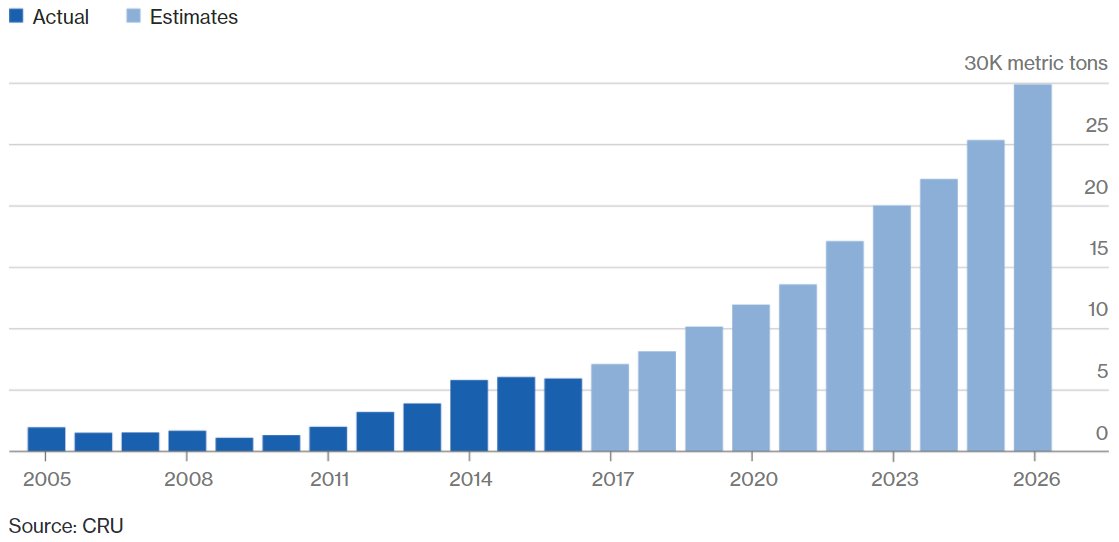

Mining Batteries

Recycling dead batteries will create alternative source of scarce minerals

To cater to the biggest market for electric cars, Chinese manufacturers are going further than many western counterparts. Great Wall Motor Co., the nation’s biggest maker of sport utility vehicles, bought a stake in Australian lithium mine developer Pilbara Minerals Ltd.

“There is concern at the far end of the supply chain about the raw material issues,” said Sam Riggall, chief executive officer of Clean TeQ Holdings Ltd., developer of the Sunrise cobalt and nickel project in the Australian state New South Wales. He’s already signed a supply deal with Beijing Easpring Material Technology Co., which makes cathodes (the positive end of a battery). Carmakers are also knocking on his door from Asia, Europe and North America.

Also getting inundated with calls is Vladimir Potanin, chairman of MMC Norilsk Nickel PJSC, which produces the most nickel in the world, as well as cobalt at plants in and around the Arctic Circle.

“Carmakers are open to different forms of cooperation,” including long-term contracts, streaming deals and joint ventures, Potanin said in an interview. “We are in talks now over those projects. But for us it’s not clear how deep we need to go.”

If history is a guide, the cobalt mania won’t last. In the early 2000s, palladium, used in catalytic converters that remove pollution from vehicle exhaust, tripled in two years on supply concerns. Carmakers eventually found ways to use less of the metal, and demand slid by a third. Ford Motor Co. was forced to write off $1 billion when its stockpile of the metal fell in value.

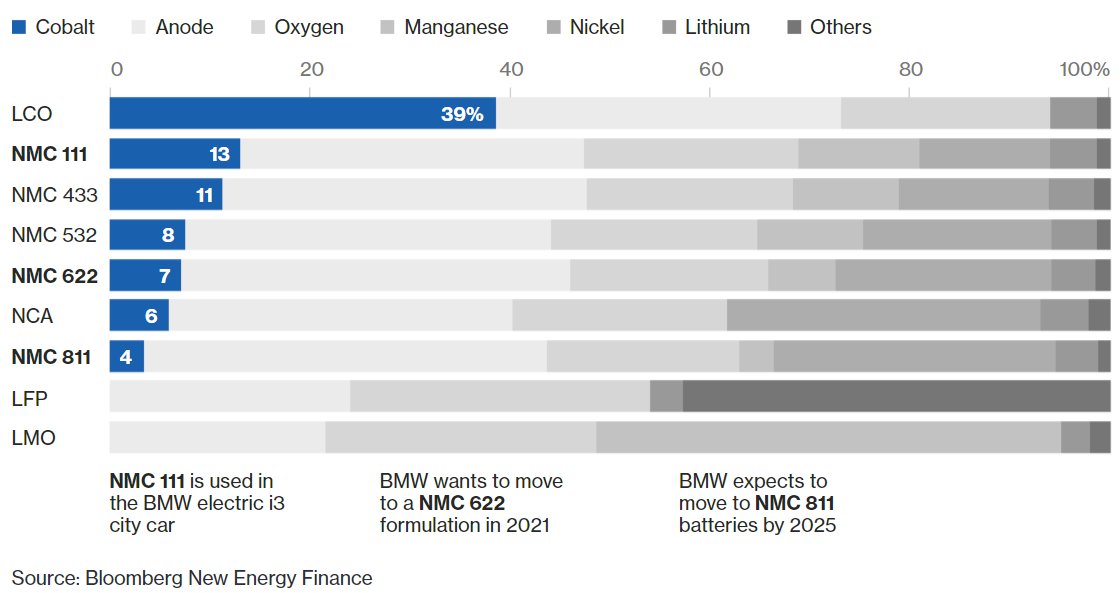

Battery Chemistries

Carmakers expect to gradually move to batteries that use less cobalt

Car-battery chemistries may follow a similar trajectory. Currently, most contain roughly equal amounts of nickel, manganese and cobalt, called NMC 111. By 2025 the dominant composition will be 80 percent nickel and 10 percent cobalt, according to UBS AG forecasts.

Recycling technologies to extract minerals from dead batteries, meanwhile, could add 25,000 tons of supply by 2025, CRU projections show.

With so much on the line, BMW’s Duesmann, a mechanical engineer who helped develop the electric i3 city car, isn’t putting too much weight on these innovations just yet. Last month, BMW revealed its dedication to an electric future by briefly lighting up its Munich headquarters, modelled in the 1970s after the four cylinders of an engine, to look like batteries instead.

“There’s going to be a supply shortage, so right now the suppliers have the upper hand,” he said.

Source: https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2018-cobalt-batteries/

By Elisabeth Behrmann, Jack Farchy and Sam Dodge

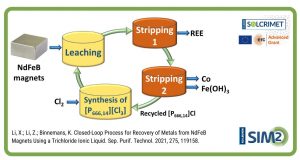

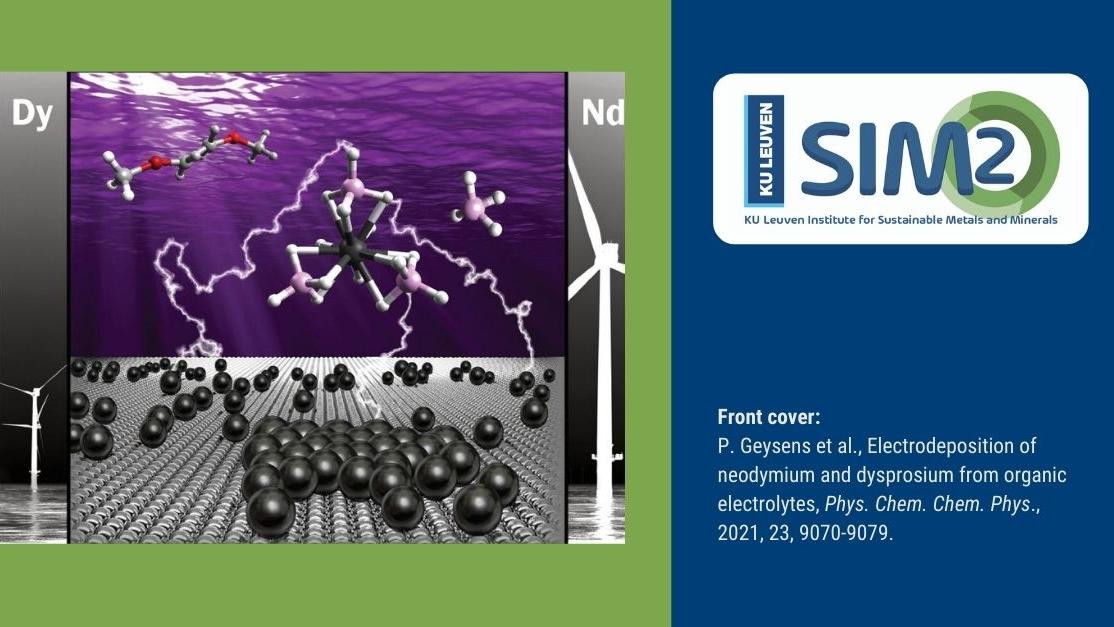

European Training Network for the Design and Recycling of Rare-Earth Permanent Magnet Motors and Generators in Hybrid and Full Electric Vehicles (DEMETER)

European Training Network for the Design and Recycling of Rare-Earth Permanent Magnet Motors and Generators in Hybrid and Full Electric Vehicles (DEMETER)