BMW Group says a fully electric three-door version of the Mini car will go into production in 2019. Photograph: Bruno Bebert/EPA

Britain last week joined France in pledging to ban sales of petrol and diesel cars by 2040 in an attempt to cut toxic vehicle emissions. The move to battery-powered vehicles has been a long time coming. Environmental campaigners claim that charging cars and vans from the grid, like a laptop, is sure to be cleaner than petrol or diesel power. The government agrees and says it will invest more than £800m in driverless and clean technology, and a further £246m in battery technology research.

BMW plans to build a fully electric version of the Mini at Cowley in Oxford from 2019. Volvo announced earlier this month that from the same year, all its new models will have an electric motor.

Huge potential profits await those that can tap into this burgeoning market. Transparency Market Research estimated the global lithium-ion battery market at $30bn in 2015, rising to more than $75bn by 2024. Morgan Stanley analysts expect global car sales to rise by 50% by 2050 to more than 130m units a year, and estimates that electric vehicles will account for at least 47% of that total.

Lithium-ion batteries have long been used to power smartphones, laptops and other gadgets. Scaled-up versions are now being developed for electric vehicles. These batteries should last for at least 10 years, or 150,000 miles, until they need to be replaced.

However, the road to a promised land of zero-emission vehicles is littered with speed bumps and red lights that threaten to seriously slow the progress of the electric car. Battery makers are struggling to secure supplies of key ingredients in these large power packs – mainly cobalt and lithium. The hopes of both battery and vehicle manufacturers hang on the mining sector finding more deposits of these precious minerals.

Trent Mell of First Cobalt, a Toronto-based mining company, said: “Cobalt is tricky because of the scarcity of supply. There aren’t a lot of producers. We’re relying on more discoveries. It’s out there: we’ve just got to find it.”

The First Cobalt boss added that his company was currently confident of making discoveries in Idaho and Ontario. Investors see a chance of cashing in on the mineral’s key role: the price of shares in the Canadian firm has risen from C$0.06 to C$0.76 in the past year.

This is the mother of supply chain headaches, and one hi-tech car manufacturers and electronics firms could do without. At the heart of the global cobalt trade is Glencore. The metals and mining giant produces almost a third (28,300 tonnes) of the world’s annual supply. As much as 65% of this global supply comes from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), where cobalt production has fallen this year because of the unstable political situation. This sparked a 90% jump in the price of cobalt to a peak of $61,000 a tonne earlier this month.

Macquarie Research predicts that trouble in the DRC and rising demand for electric vehicles will lead to a four-year-long cobalt shortage. Writing in academic journal The Conversation, Ben McLellan, senior research fellow at Kyoto University, warned further: “Manufacturers such as electric vehicle makers should be concerned that the supply of one of the key mineral components, or the processing and refining infrastructure, could become too centralised in a single country. Without diverse source options, the possibility of supply restriction becomes more likely.”

The squeeze on cobalt has sent car giants such as Volkswagen scurrying to lock in supply deals with the likes of Glencore. First Cobalt’s Mell said: “I think there is going to be some jockeying for supply.”

Volkswagen, which had been slow to develop battery-powered vehicles, it is now pushing through an ambitious programme as it seeks to regain the trust of customers and investors after the diesel emissions scandal. The German manufacturer wants to launch more than 10 electrified models by the end of next year and is aiming at 30 battery-powered models by 2025. It plans to increase electric-car sales to a million a year by 2025, from tens of thousands at present.

Demand for other key battery ingredients, such as graphite and lithium carbonate, is also outstripping supply. The current shortage of lithium has seen prices double since 2015. Global lithium demand was 184,000 tonnes in 2015, with battery demand accounting for 40%. Analysts at Deutsche Bank expect demand to increase to 534,000 tonnes by 2025, with battery manufacturers accounting for 70%. Lithium deposits are found mostly in China and Bolivia.

Two South Korean battery makers – Samsung SDI and LG Chem – have responded to the crisis by stepping up development of new power packs that use more nickel and less cobalt.

Other battery pioneers are trialling alternative materials in an attempt to crack the booming energy storage market. In June, the US Naval Research Laboratory signed a commercial licensing agreement with California-based EnZinc. This firm was co-founded by Michael Burz, who worked previously on the design of the Tomahawk cruise missile as well as for Nissan.

The agreement gives EnZinc exclusive rights to a nickel-zinc battery for use in electric road vehicles, to hybrid cars that use that battery, and microgrids (small localised electric grids that can run independently) of up to 60 megawatts. Burz expects his zinc-based battery technology to be ready for market in about two years, with another year to gear up production.

Lithium-ion batteries can include other materials such as magnesium, cadmium, manganese and cobalt oxide. They also use a flammable electrolyte, which makes them more risky than lead-acid batteries. EnZinc’s solution is to incorporate less-volatile metals – zinc and nickel – in a battery with sponge-like silicon electrodes.

A key advantage of EnZinc’s plan is that zinc is in much more plentiful supply than cobalt and lithium. Deposits of the metal are found in China, Australia, Peru and the US among others. The US alone produces about 900,000 tonnes of zinc a year, much of it from the huge Red Dog Mine in Alaska, operated by Vancouver-based Teck Resources. It is thought around 600,000 tonnes of zinc would be required to make batteries for a million electric vehicles. One large international zinc company mines around 14m tonnes a year.

But while big corporations work on a green energy revolution, Amnesty International has shone a light on the dark side of this dream. The human rights group says children as young as seven continue to work in perilous conditions in mines in the DRC.

In 2014, according to Unicef, about 40,000 children were working in mines across southern DRC, many of them extracting cobalt. A report by Amnesty and Afrewatch (African Resources Watch) published in January said corporations such as Apple, Samsung, Sony, Microsoft, Daimler and Volkswagen were failing to do basic checks to ensure that they did not use cobalt mined by child labourers in their products.

Mark Dummett, business and human rights researcher at Amnesty International, said: “The glamorous shop displays and marketing of state-of-the-art technologies are a stark contrast to the children carrying bags of rocks, and miners in narrow manmade tunnels risking permanent lung damage.

“Millions of people enjoy the benefits of new technologies but rarely ask how they are made. It is high time the big brands took some responsibility for the mining of the raw materials that make their lucrative products.”

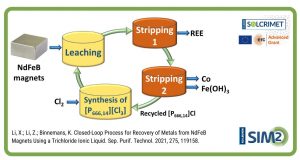

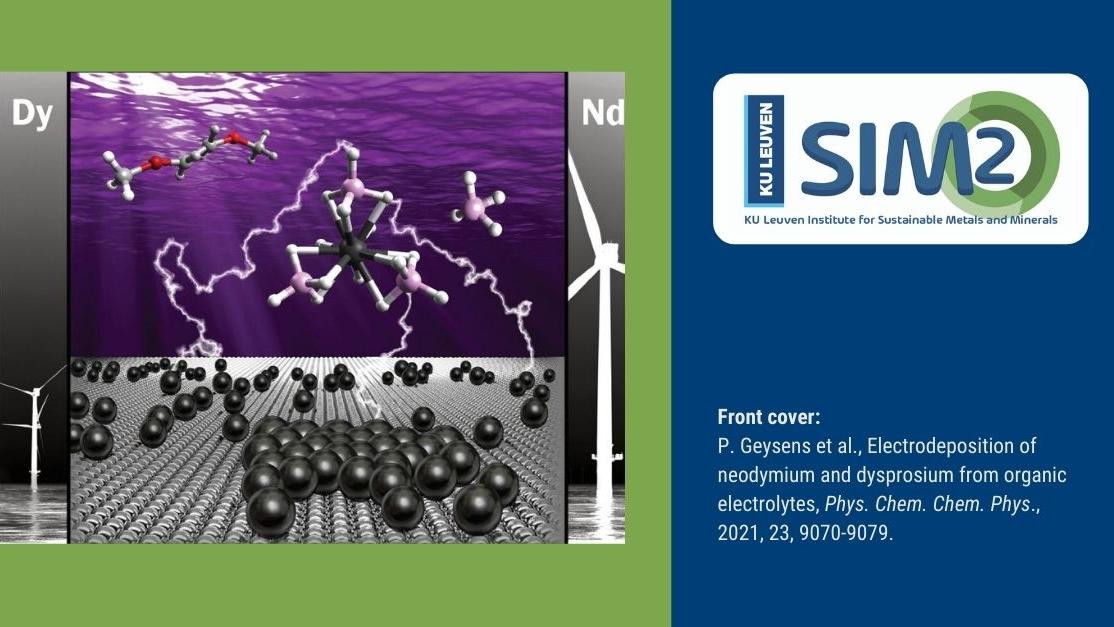

European Training Network for the Design and Recycling of Rare-Earth Permanent Magnet Motors and Generators in Hybrid and Full Electric Vehicles (DEMETER)

European Training Network for the Design and Recycling of Rare-Earth Permanent Magnet Motors and Generators in Hybrid and Full Electric Vehicles (DEMETER)