Are electric cars ready to stand on their own?

If you took a spin down to the New York auto show and saw the $37,500 Chevy Bolt (electric) parked next to the strikingly similar $17,000 Chevy Cruze (gasoline), the answer is probably a hard “no.” The Bolt is arguably a better car than the Cruze — but not $20,000 better.

Edmunds recently weighed in with a hard “no” of its own, warning that the elimination of a $7,500 U.S. tax credit is “likely to kill [the] U.S. EV market.” Edmunds pinned its argument on what happened in Georgia, a state that became a leader in electric cars thanks to an extra $5,000 incentive. At one point, almost four percent of new cars being sold in Georgia were electric. Then they pulled away the punch bowl.

Chevy Bolt

But a very illuminating thing happened after Georgia’s incentives expired. Unlike the Nissan Leaf, which made up the majority of the EV market there, sales of luxury-market Teslas were barely affected by the loss of the tax credit. In fact, more people are buying Teslas in Georgia today than during the subsidy years.

The Tesla exception shows what happens when an electric car reaches parity with fuel-burning competitors in both price and function. Unlike the Leaf and the BMW i3, the Tesla Model S is quicker than similarly priced gasoline cars, has a long driving range, extensive fast-charging network, and is packed with tech advances like Autopilot and wireless software updates.

Changes to state or federal incentives are unlikely to alter Model S sales. But those Teslas are premium cars that start around $70,000. For plug-ins to really pass the subsidy test and take over the auto industry, they’ll need to prove themselves in cheaper classes of car, and there will have to be more manufacturers besides Tesla.

When might that happen?

The primary cost for an electric car is its battery, responsible for almost half the price of a midsize plugin. If you take that away, electric cars are much cheaper to produce and maintain than internal combustion vehicles. (That’s why French carmaker Renault sells its popular Zoe without a battery, which customers pay a monthly fee to lease.)

For true mass-market appeal, the upfront sticker price is what matters most, and battery prices must come down further. Fortunately, prices are falling fast — by roughly 20 percent a year. The manufacturing cost of electric cars will fall below their gasoline counterparts across the board around 2026, according to a recent analysis by Bloomberg New Energy Finance.

The question of when electric cars will cost the same as their combustion counterparts isn’t academic. The $7,500 federal incentive is set to taper off as each manufacturer reaches its 200,000th U.S. sale. For Tesla, that day will arrive sometime next year. Nissan and General Motors won’t be far behind — and any extension of the subsidy by the Trump administration seems unlikely.

Another thing that makes electric cars more expensive is that, at lower volumes (less than 100,000 a year of the early models), even the traditional components of a car come at higher costs. Low production numbers and high battery development costs created a valley of despair for EVs that lasted decades, which is why subsidies have been critical to giving the sector enough breathing room to eventually stand on its own.

Government incentives were crucial to the birth of the EV industry, and many countries and local governments will continue to offer them because of the critical role electric cars play in reducing pollution and combatting climate change.

But even where governments are less enlightened, the valley of despair is coming to an end. Tesla, the first to approach price and function parity in the Model S sedan and Model X crossover, will attempt to recreate that magic later this year with the Model 3, a $35,000 entry-level luxury sedan. A longer-range Nissan Leaf will be unveiled in September, and depending on its price, it could begin to approach the parity zone in the sub-$30,000 market.

And then watch out: In 2018, Volkswagen plows into electrification with an Audi crossover and the first high-speed U.S. charging network to rival Tesla’s Superchargers. Jaguar and Volvo both have promising cars on the way too, and by 2020, the avalanche really begins, with Mercedes, VW, GM and others releasing dozens of new models.

When the U.S. incentives begin to expire next year, don’t expect a Georgia-sized collapse in the market. The period of greatest peril is ending for EVs, and the time of greatest promise is beginning. All the top carmakers are investing billions of dollars to electrify their drivetrains, and the smart ones will compete aggressively on pricing in the short-term in order to establish market share for the long haul. Incentives are important, but they won’t define the market for much longer.

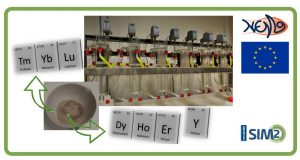

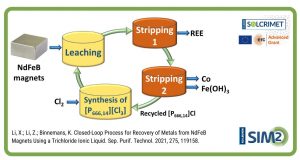

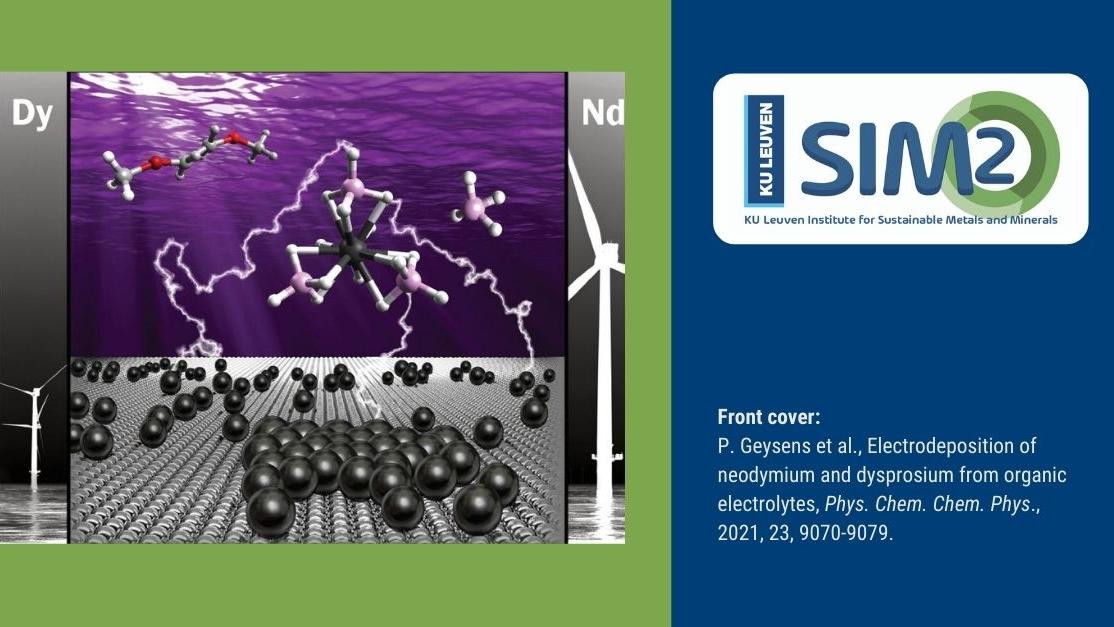

European Training Network for the Design and Recycling of Rare-Earth Permanent Magnet Motors and Generators in Hybrid and Full Electric Vehicles (DEMETER)

European Training Network for the Design and Recycling of Rare-Earth Permanent Magnet Motors and Generators in Hybrid and Full Electric Vehicles (DEMETER)